Blog

Ultimate Guide to Foreign Trade Zones

When high-performance outerwear manufacturer Helly Hansen set out to revamp its North American distribution system, the Norway-based company thought it made sense to consolidate operations in its existing warehouse located in British Columbia, Canada. This was thought to be a logical decision since the company had recently been acquired by a Canadian company and because it had a larger market share in Canada than in the United States.

However, the manufacturer soon realized a tremendous opportunity that was hiding in plain sight: one of its existing warehouses in Auburn, Washington, was located in proximity to the Seattle Foreign-Trade Zone (FTZ #5), which offered the potential for significant cost savings and supply-chain efficiencies.

After a careful cost-benefit analysis, Helly Hansen management submitted an application to the controlling Foreign-Trade Zones Board (FTZ Board), and following approval and a meticulous planning process, the company activated its FTZ “subzone” and began to reap the savings. Millions of dollars in savings. The company has benefitted from unique opportunities to defer duty payments, pay reduced duty amounts, and, in some instances, avoid paying any duties at all. In addition, it has dramatically reduced customs brokerage fees and also helped drive down transportation costs by 40–60 percent.

The manufacturer’s experience was so successful that it found itself in need of a larger warehouse, which it found in Foreign-Trade Zone #86 — the Port of Tacoma. The company subsequently moved its consolidated operations to the larger facility in 2016.

With its decision to utilize the Foreign-Trade Zone program, Helly Hansen joined a growing number of businesses that have recognized the benefits of this important — but not well understood — incentive program.

Administered by the Foreign-Trade Zones Board, which is part of the U.S. Department of Commerce, foreign-trade zones are areas within the United States that are considered to be outside of U.S. customs territory. Certain types of merchandise can be imported into an FTZ without going through formal customs entry procedures or paying import duties. Customs duties and excise taxes are due only at the time materials leave the FTZ and enter U.S. commerce. If the merchandise never enters U.S. commerce, then no duties or taxes are paid on those items.

With such lucrative benefits, it’s not surprising that FTZs have become integral to the U.S. economy. The National Association of ForeignTrade Zones (NAFTZ), in its 2018 Annual Report, notes that goods exported directly from U.S. FTZs exceeded $75 billion, an amount equivalent to 5.2 percent of total merchandise exports. Further, NAFTZ found that in 2017, the value of shipments into zones totaled $670 billion, of which $410 billion (61 percent) was for production operations and $259 billion (39 percent) for warehouse/distribution operations.

“The U.S. FTZ program continues to demonstrate its value to the U.S. economy,” NAFTZ President Erik Autor said in the Annual Report. “Companies in many key American industries, including oil refining, automotive, electronic, pharmaceuticals, and machinery/equipment, gain significant global competitive advantage by locating their production and distribution operations in U.S.-based FTZs, thereby boosting American exports, manufacturing, investment, jobs, and standard living.”

As beneficial as FTZs can be, they are not for everyone. For one thing, there are cost and time commitments associated with the application process, including FTZ Board and U.S. Customs and Border Protection requirements. Other considerations include procuring physical assets, development of operational materials, and staff training. This is in addition to ongoing compliance and reporting requirements.

Businesses, especially high-volume importers and exporters, that do successfully implement foreign-trade zones stand to reap significant cost savings and operational efficiencies. The process starts with an understanding of the FTZ program, including its origins, benefits, and mechanics. The following discussion will shed light on these and other significant aspects, which are important considerations in determining the feasibility of the Foreign-Trade Zone program for a particular business.

What Is a Foreign-Trade Zone?

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), foreign-trade zones (FTZs) are secure areas that are generally considered to be outside U.S. customs territory for duty assessments and other customs entry procedures. Specifically, zones are physical areas into which foreign and domestic merchandise may be moved for lawful operations, including storage, exhibition, assembly, manufacture, or processing. FTZs are licensed by the ForeignTrade Zones Board and operated under the supervision of CBP.

Foreign-trade zones offer a range of financial benefits to companies by allowing them to reduce, eliminate, or defer duty payments on goods manufactured or stored in FTZs before they enter U.S. commerce or are exported. Located in or near CBP ports of entry, foreign-trade zones are the United States’ version of what are known internationally as free-trade zones.

As noted by the FTZ Board: “Zones have as their public policy objective the creation and maintenance of employment through the encouragement of operations in the United States, which, for customs reasons, might otherwise have been carried on abroad.”

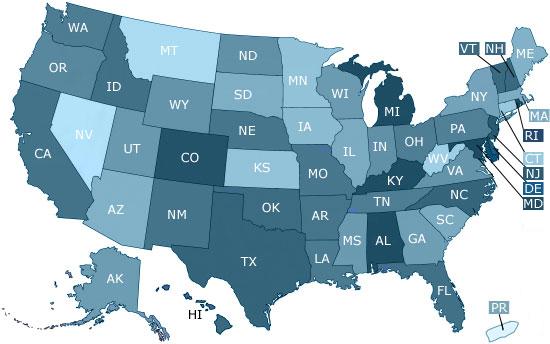

Foreign-trade zones were authorized by the U.S. Congress under the Foreign-Trade Zones Act of 1934 as a way to expedite and encourage international commerce. Although U.S. businesses failed initially to embrace FTZs, the concept has taken hold, especially over the last 30 years. According to the Foreign-Trade Zone Corporation, in 1970 there were eight U.S. FTZ projects, whereas today the Foreign-Trade Zones Board lists more than 250 authorized FTZs, with at least one in each state and in Puerto Rico. In addition, there are almost 500 “subzones,” which are individual businesses or manufacturing facilities.

Although FTZs have broad appeal across many sectors, CBP cites the petroleum refining industry as the largest zone user, along with the automotive, electronic, pharmaceutical, and machinery/equipment industries. The 2018 NAFTZ Annual Report notes that during 2017, roughly 3,200 businesses were actively using FTZs.

A 2019 update by the FTZ Board provides a partial listing of U.S. companies currently benefitting from FTZ participation. That list includes:

- Automobile Manufacturers: BMW, Ford, General Motors, Mercedes-Benz, Tesla, Honda, Hyundai, Nissan, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Volvo.

- Oil/Petroleum: ExxonMobil, British Petroleum, Chevron, Citgo, Marathon Oil, Phillips 66, Shell Oil, Sunoco, and Valero.

- Pharmaceutical Manufacturers: Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Baxter International, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Co., GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck & Co.

- Consumer Products: Bell Sports, Black & Decker, Callaway Golf, Citizen Watch, Conair, Mr. Coffee, Oneida, SentrySafe, Tiffany & Co., and Walmart.

- Industrial/Machinery Equipment: Becker Hydraulics, Deere & Company, Kubota, Liberty Pumps, and Makita.

- Semiconductors: Intel, Samsung, Microchip Technology Inc., and SUMCO Southwest Corporation.

- Electronics/Telecommunications Manufacturers: Avaya, Cornell Dubilier, Isola USA, IBM, and Lucent.

Types of ForeignTrade Zones

A business considering the merits of the FTZ program will need to be familiar with the different types and subcategories of foreign trade zones. CBP designates two main categories of FTZs:

General Purpose Zones: Usually located in an industrial park or port complex with facilities available for use by the general public.

Subzones: Sites sponsored by a general-purpose zone that are normally for a single-purpose and cannot be moved or accommodated in a general-purpose zone. An individual company’s qualified warehouse is a common example of an FTZ subzone.

Alternative Site Framework: The FTZ Board attempted to add flexibility to zone management when, in 2008, it approved the “alternative site framework” (ASF) option. According to the Foreign-Trade Zone Corporation, the ASF option provides previously approved FTZ grantees with a streamlined process for expanding operations within their established service area. A zone grantee that wishes to accommodate either an existing site user or a new user can utilize ASF’s “minor boundary modification” process, which provides accelerated review by the FTZ Board, with approval likely within 30 days.

Helly Hansen took advantage of the ASF option in having its Auburn, Washington, warehouse designated as an FTZ subzone. The outerwear manufacturer’s FTZ application process began by gaining approval from the Port of Seattle, which is the grantee for Foreign-Trade Zone #5. Once that approval was obtained, the Port of Seattle then submitted a “request for minor boundary modification” on behalf of Helly Hansen. Using this process, the time to approve zone status was reduced from 8-12 months to 30 days.

Businesses interested in the ASF option may encounter terms that include the following, as defined by the International Trade Administration:

- Service Area: Refers to the geographic area where a grantee seeks to propose sites for specific users. May consist of a single warehouse, industrial park, or an air or seaport complex whose facilities are available for use by the public. Service areas are generally used for warehousing, but manufacturing authority may be obtained by a single company via a separate application to the FTZ Board. A service area site must meet FTZ adjacency requirements (located within 60 miles, or 90 minutes driving time, of a CBP port of entry).

- Magnet Site: A site selected based on its ability to attract multiple potential FTZ operators/users

Usage-Driven Site (Subzone): Designation tied to a named company and limited to the space needed for that company’s use. If the named company vacates its usage-driven site, the FTZ designation automatically terminates. (Similar to definition for subzones located in non-ASF FTZs.)

Foreign-Trade Zone Structure and Compliance

U.S. Customs and Border Protection

Once a zone location has been established by the FTZ Board, companies are required to “activate” the zone with CBP prior to beginning FTZ operations. According to CBP, oversight responsibilities include:

- Responsibility for the transfer of merchandise into and out of the zone, and for matters involving the collection of revenue.

- Legal interpretations of applicable statutes and regulations.

The CBP port director, in whose port a zone is located, serves as the local representative of the FTZ Board and is responsible for day-to-day zone activities. The port director controls the admission of merchandise into the zone, the handling and disposition of merchandise in the zone, removal of merchandise from the zone, and compliance with all applicable laws.

Foreign-Trade Zone Benefits

Businesses that take advantage of FTZs can avail themselves of a multitude of benefits that can help drive down — in some cases eliminate — duty payments, and improve supply chain operations. With regard to the previously cited Helly Hansen example, analysis by The Trade Partnership cited $200,000 in annual savings along with logistics efficiencies the company is able to achieve through use of an FTZ. Those savings opportunities include:

- Approximately 55 percent of products imported into the company’s Port of Tacoma (FTZ #86) warehouse are subsequently exported to Canada. Helly Hansen pays no import duties on those products.

- The company does pay import duties on products destined for the U.S. market but not until the products leave the FTZ. Thus, the company is able to defer duty payments while products are stored in its FTZ-located warehouse (estimated 2018 savings: $65,000).

- Once products are ready to leave the FTZ and enter U.S. commerce, the company is able to bundle the goods into a single shipment and clear customs as a single entry. This allows the company to avoid having the required merchandise processing fee applied to each entry (estimated 2018 savings: $128, 500).

- The company is also exempt from duty payments on FTZ-located goods that become damaged and need to be destroyed (estimated 2018 savings: $6,000).

The National Association of Foreign-Trade Zones provides an overview of common FTZ benefits and opportunities that include:

- Duty Deferral Benefits. Instead of paying U.S. duty when a shipment arrives in the U.S., duty payment is deferred until the goods are actually transferred from the zone into the U.S. market, providing valuable cash-flow benefits. Goods may be stored indefinitely in an FTZ.

- Duty Reduction (Inverted Tariff). Businesses utilizing a particular FTZ can petition the Board to use a certain “zone status” on merchandise admitted to the zone. This zone status determines the duty rate that will be applied to foreign merchandise should it eventually enter the U.S. market from the FTZ. Through this process, a business can elect to pay either the duty rate applied to foreign components placed in the zone or the duty rate applicable to the finished product transferred from the zone — whichever is lower. The General Accounting Office, in a 2017 assessment of FTZ zones, presented a case study illustrating this benefit:

The duty rate to import foreign-sourced microcrystalline cellulose is 5.2 percent. However, a company can use it to manufacture a final product such as dietary supplement capsules in a foreign-trade zone and import the capsules into U.S. commerce with a duty rate of 0.00 percent. If 50 percent of each capsule is foreign-sourced microcrystalline cellulose, and if Company A imports $1.5 million worth of capsules each week, it can save $39,000 per week in duty payments, about $2 million per year.

- Elimination of Duties. Since no duty is paid on merchandise exported from an FTZ, duty is effectively eliminated on foreign merchandise admitted to a zone that is eventually exported from an FTZ. Duties are also eliminated on merchandise that is scrapped, wasted, destroyed, or consumed in a zone.

- Elimination of Duty Drawback. In some instances, businesses are able to recoup import duties and fees paid on products that are subsequently exported. That reimbursement is called a duty drawback. However, the process for applying for drawback can be complicated and timeconsuming. Businesses that utilize FTZs may be able to avoid having to apply for drawback by avoiding payment of duties in the first place. That way, funds that would have been tied-up in “customs limbo” can remain in a business’ cash flow.

- Reduced Customs Fees. A Merchandise Processing Fee (MPF) is assessed by CBP on every shipment valued at $2,500 or more entering an FTZ. The MPF is an ad valorem fee assessed at a rate of 0.3464 percent of the value of the merchandise being imported. MPF “rules” provide that fees range from a minimum of $25 to a maximum of $485. However, FTZ users are now able to file a single entry for all goods shipped from a zone in a consecutive seven-day period. This is a significant change from previous rules that required each shipment to have its own entry. Since the maximum MPF is $485 per entry, a business can significantly reduce its fee obligations.

- State and Local Taxes. Personal property imported from outside the United States and held in an FTZ, as well as products made in the U.S. and held in a zone for exportation, benefit from a federal preemption from state and local ad valorem personal property taxes. In some cases, businesses may also benefit from statespecific tax reductions.

- Labor and Overhead Costs. Zone users are authorized to exclude costs associated with processing or fabrication, general expenses, and profit. Therefore, duties are not owed on labor, overhead, and profit attributed to merchandise produced in an FTZ.

- Cash-Flow Savings. 2019 analysis by The Trade Partnership cited the potential for a company to realize significant cash flow efficiency through use of a FTZ. “Customs duties are paid only when and if the goods exit the zone for entry into the U.S. customs territory for consumption,” the report noted. “While the goods are in storage (there is no time limit for how long imported merchandise can remain in the FTZ), companies can, for example, inspect them and only later enter those that pass inspection. This benefit is of particular value to retailers, to companies with higher capital costs, and to those who import goods subject to quotas.”

- Streamlined Logistics. FTZ users can take advantage of direct delivery whereby imported goods move directly from the port of unloading to the distribution center, thereby eliminating certain customs-related delays. For companies moving products from the West Coast to East Coast, direct delivery can save days.

Becoming a Foreign-Trade Zone

According to the FTZ Board, a foreign-trade zone is created when “a local organization, such as a city, county or port authority, applies to the FTZ Board for a grant to establish and operate a zone to serve a specifically defined geographic area.” Upon approval of the zone by the FTZ Board, the organization becomes known as the FTZ “grantee.” Grantees are then able to submit applications to the FTZ Board to establish subzones for use by companies in that area. In addition, a company can apply to designate only a part of its facility as an FTZ.

In some instances, an entity may opt to file as an “alternative site framework” (ASF), which allows zones to use quicker and less complex procedures to obtain designation for eligible facilities.

- Pre-Docketing. The process begins with submission of a complete application to the FTZ Board.

- Docketing. When an application is docketed by FTZ staff, a notice is published in the Federal Register for public comment on the proposal. The public comment period usually lasts 60 days for an FTZ application or 40 days for a subzone application.

- Review. The application is reviewed by FTZ staff.

- Interagency Clearance. Once FTZ staff completes its review and proffers a recommendation, the application is sent to CBP and the Department of Treasury. If both agencies concur with the FTZ staff recommendation to proceed, the application is returned to the Department of Commerce for final review and, potentially, issuance of a Board order. The Board order is subsequently published in the Federal Register.

Businesses must follow the application process established by the ForeignTrade Zones Board.

Implementation and Activation Phases

A business must also comply with “implementation phase” requirements, which can be initiated concurrent with the application phase. This includes coordination with CBP to ensure that proper security controls and site prerequisites are in place that may include:

- Development of Process Manual

- Staff training

- Security controls, including employee background checks

- Certificate of Insurance

- Customs Bond

- Operations agreement document with the grantee that outlines each party’s roles and responsibilities

- Establishment of an FTZ inventory technology system

Once the application is approved and all requirements have been addressed, the FTZ applicant will conduct a final walkthrough with CBP personnel to confirm full compliance with all requirements. CBP will then issue an “activation letter.” At this point, the company is authorized to begin using its foreign-trade zone.

How Does a Foreign-Trade Zone Operate?

According to the Foreign-Trade Zones Board, foreign and domestic merchandise may, subject to FTZ Board and CBP regulations, “be moved into zones for operations not otherwise prohibited by law involving storage, exhibition, assembly, manufacturing, and processing.” All FTZ sites are subject to the laws and regulations of the United States as well as those of the states and communities in which they are located.

International law expert Sandler, Travis & Rosenberg explains that the director of the CBP port in which an FTZ is located controls the admission of goods into the zone, the handling and disposition of goods in the zone, and the removal of goods from the zone. Zones are supervised by FTZ coordinators, which may include CBP officers, import specialists, entry specialists, or agricultural specialists, among other professionals.

Goods entering an FTZ are not subject to usual entry procedures. Further, payments of duties are not required on foreign goods unless and until they enter the U.S. customs territory for domestic consumption, at which point the importer generally has the choice of paying duties at the rate of either the original foreign materials or the finished product. Domestic goods moved into the zone for export may be considered exported upon admission to the zone for purposes of excise tax rebates and drawback.

Allowable Activities within an FTZ

According to the International Trade Administration, when a company receives authority from the FTZ Board, it must closely adhere to the precise scope of activities included in the application and must only allow entry to the listed finished products and foreign-status components.

Production in a zone may include traditional manufacturing activities as well as kitting or assembly applications. However, if activity within a zone results in a change in a product’s tariff classification code, or a “substantial transformation,” specific approval will be required from the FTZ Board.

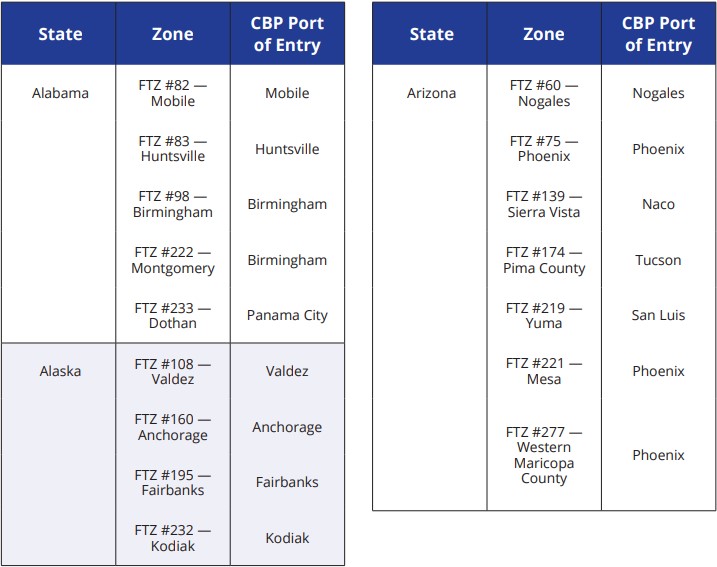

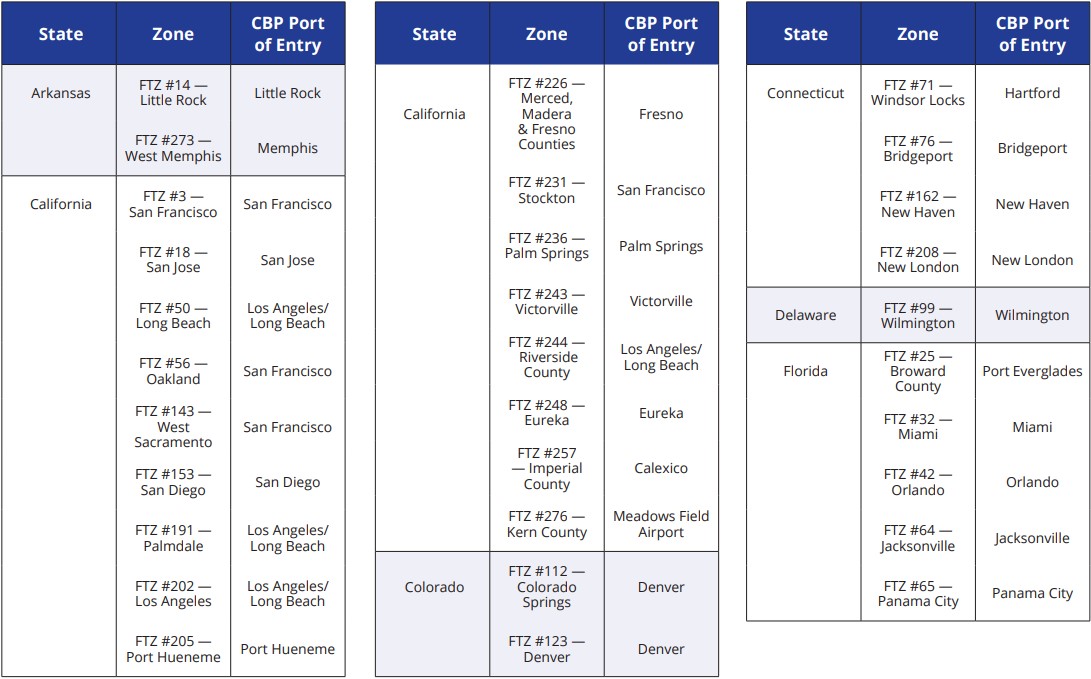

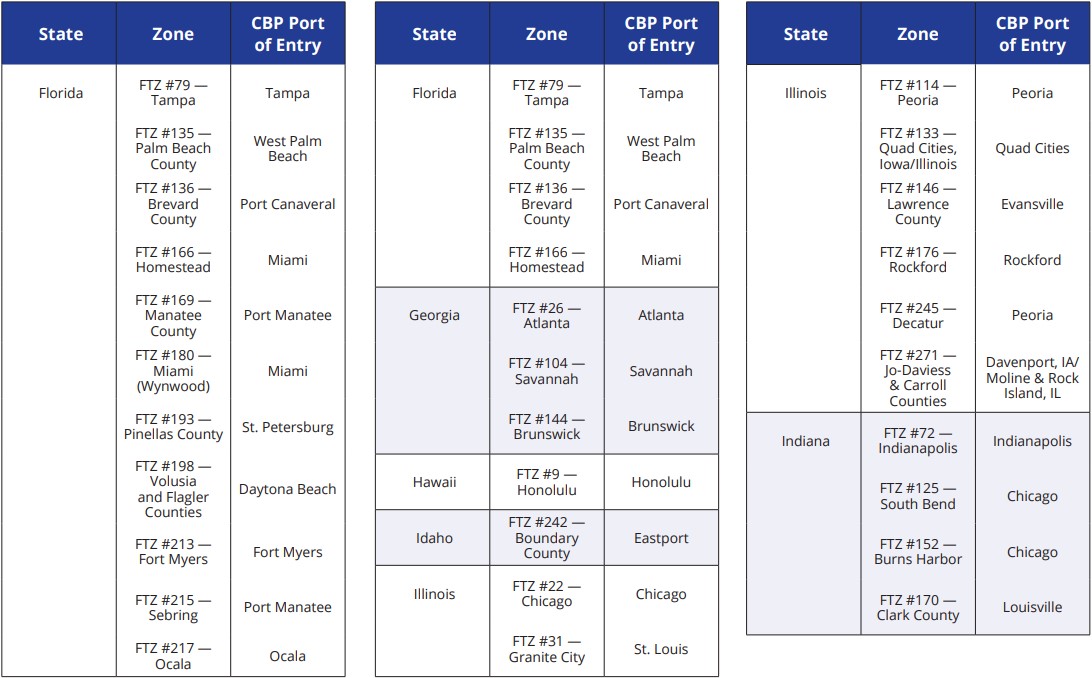

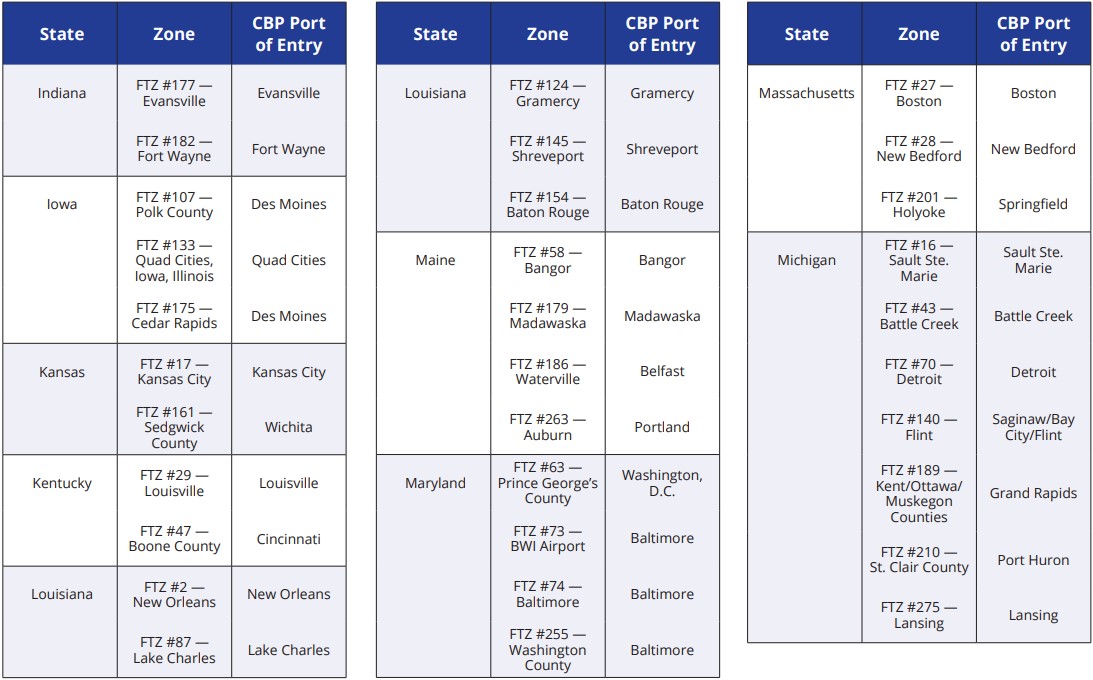

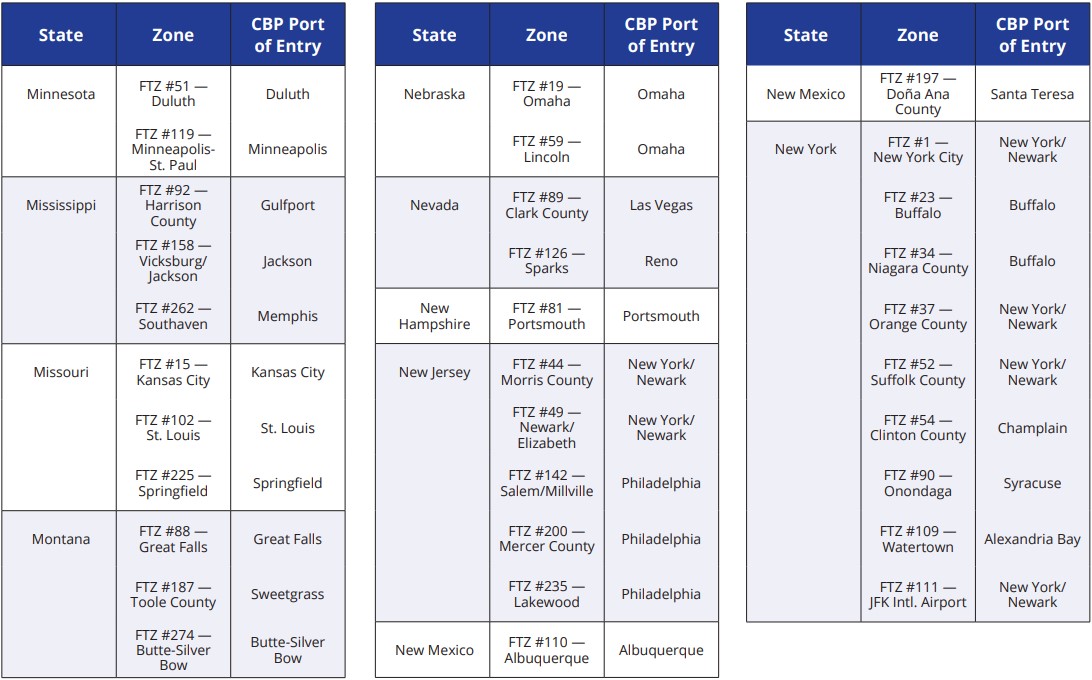

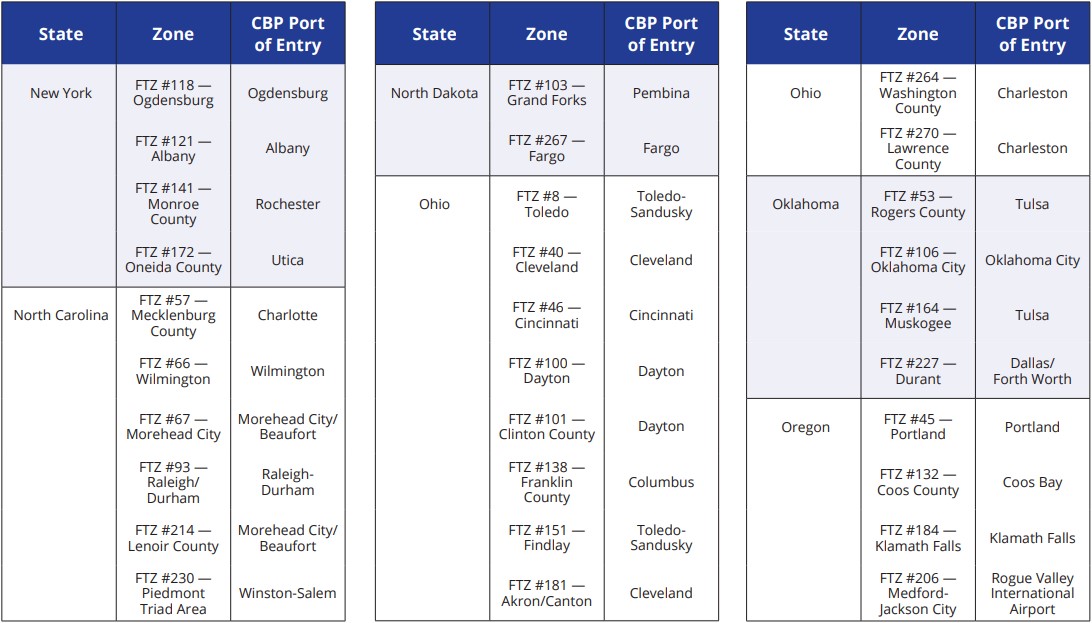

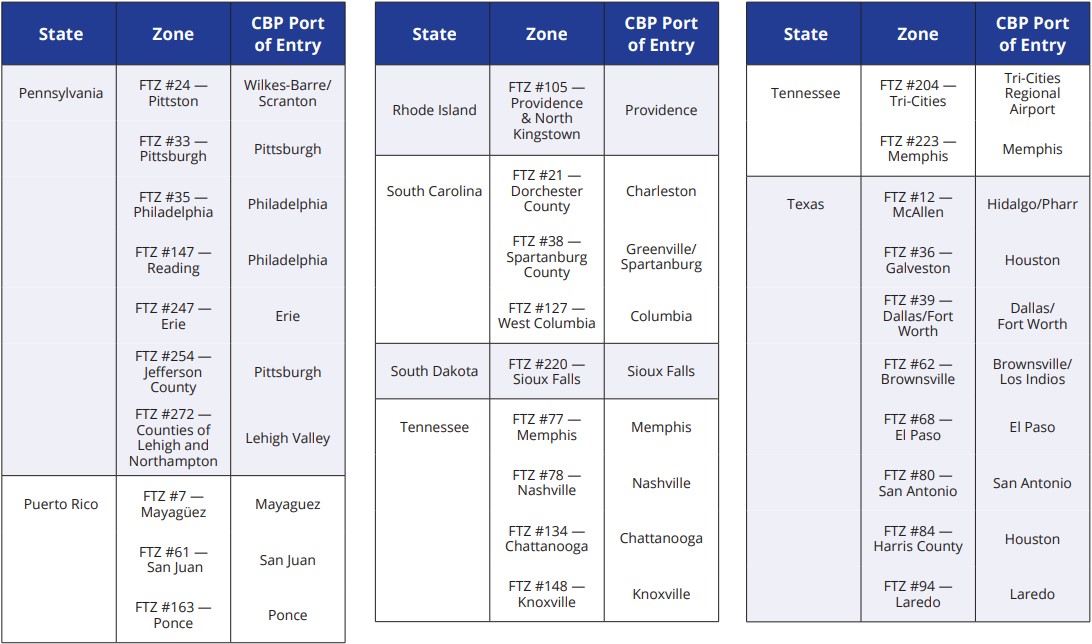

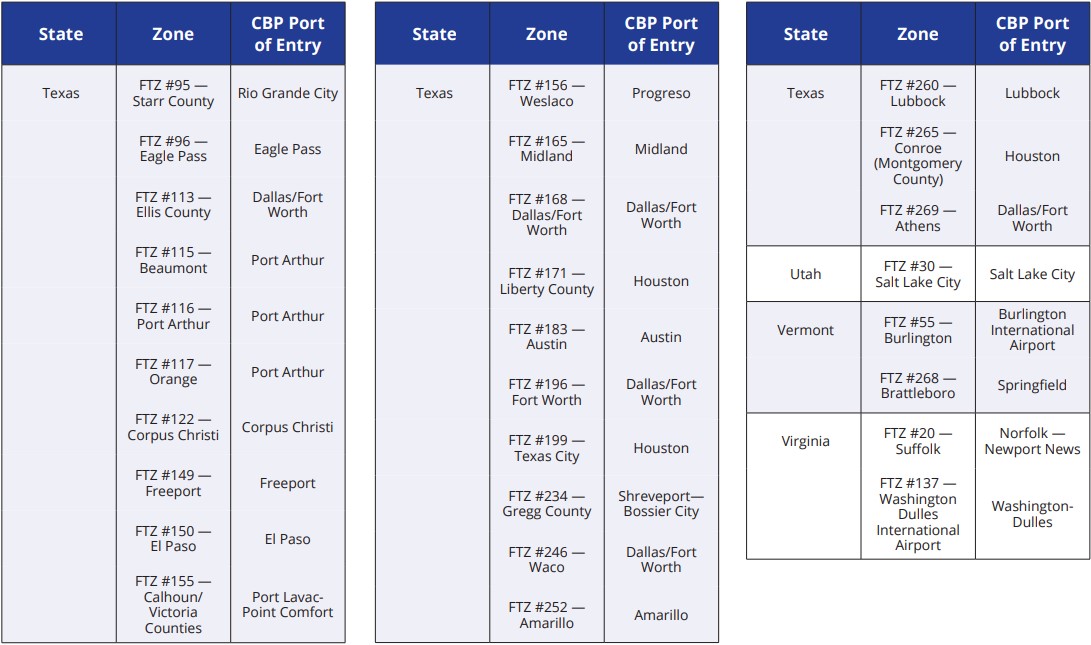

Where Are Foreign-Trade Zones Located?

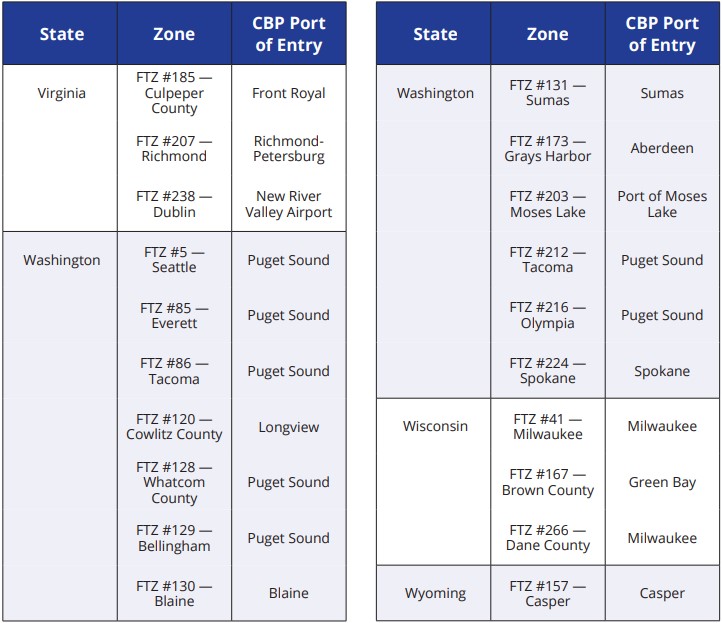

Following is the list of current U.S. foreign-trade zones (not including subzones), as published by the U.S. International Trade Administration:

Conclusion

In compiling a 2019 analysis of the impact FTZs have on the companies using them, researchers from The Trade Partnership spoke directly with hundreds of companies to learn firsthand about the benefits — or obstacles — of using an FTZ. Among the findings:

- BMW found that its FTZ operations directly and indirectly add $6.3 billion annually to the state of South Carolina and led to the employment of more than 36,000 people in the state. Nationwide, BMW says it has added almost $16 billion in value and helped create 120,000 jobs.

- ExxonMobil claims one out of every eight jobs in the Baton Rouge, Louisiana, area can be traced back to the company.

- Yamaha Motors noted that roughly 30 percent of the parts and components used to make its products in the FTZ come from Georgia-based suppliers, with another 20 percent coming from other U.S. suppliers.

- Helly Hansen says that because of the benefits afforded by the FTZ, it was able to keep jobs in the United States, despite strong pressure to move them to an international venue.

- Prodeco Technologies, a Florida-based electric bike manufacturer, uses its FTZ duty savings to keep its finished bike prices competitive with foreign-assembled eBikes that can be imported in the United States duty-free.

Clearly, FTZs can be a win-win in helping U.S. businesses compete in today’s increasingly global marketplace. U.S. businesses benefit from significant duty savings and logistical efficiency, while the American economy benefits from a boost in manufacturing, job creation, and increased revenue sources. But the decision to pursue an FTZ strategy is not without risk and will incur significant investments in time and resources. This means conducting a thorough cost-benefit analysis to ensure it’s the right decision. But given the potential benefits, it could be time well spent.

Purolator. We deliver Canada.

Purolator is the best-kept secret among leading U.S. companies who need reliable, efficient, and cost-effective shipping to Canada. We deliver unsurpassed Canadian expertise because of our Canadian roots, U.S. reach, and exclusive focus on cross-border shipping.

Every day, Purolator delivers more than 1,000,000 packages. With the largest dedicated air fleet and ground network, including hybrid vehicles, and more guaranteed delivery points in Canada than anyone else, we are part of the fifth-largest postal organization in the world.

But size alone doesn’t make Purolator different. We also understand that the needs of no two customers are the same. We can design the right mix of proprietary services that will make your shipments to Canada hassle-free at every point in the supply chain. Contact us today!